- Obtain urgent surgical consultation and administer early antibiotics for patients presenting with signs of bowel ischemia or sepsis.

- Give fluid resuscitation to patients presenting with hypovolemia or signs of shock, with pressors as needed.

- Provide symptomatic therapy with intravenous (IV) pain medication and antiemetics.

- Give the patient nothing by mouth.

- Gastric decompression with a nasogastric tube (NGT) is not recommended in all cases but may assist in patients with severe abdominal distension.

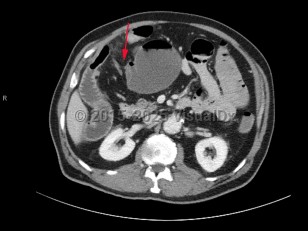

A small bowel obstruction (SBO) occurs when intraluminal bowel contents fail to pass through the small intestine. Impaired passage of bowel contents results in dilation of the proximal bowel, with fluid accumulation, gas production, increased intraluminal pressure, and bacterial overgrowth. This results in abdominal distension and pain, nausea, and vomiting, with risk of bowel ischemia and perforation.

SBOs are defined by the etiology (mechanical or functional) and severity (complete or partial).

Common etiologies include:

- Postoperative adhesions (most common)

- Incarcerated or strangulated hernia (second most common)

- Midgut volvulus

- Intussusception

- Tumors

- Intraluminal foreign bodies, such as gallstones

- Compression from extraluminal masses

- Ingestion of multiple magnets

SBOs can be classified as partial or complete. Partial SBOs permit some passage of bowel contents past the obstruction site, while complete SBOs are associated with the inability to pass any gas or fluid past the obstruction. Partial SBOs can further be stratified into high-grade or low-grade, depending on the severity of obstruction, with low-grade SBOs presenting with less severe symptoms. A simple SBO is characterized by a single point of obstruction. A closed-loop obstruction is characterized by occlusion of the bowel at 2 points and has the highest risk of ischemia due to occlusion of the blood supply.

Patients most commonly present with diffuse or periumbilical abdominal pain, often described as colicky, with paroxysms every few minutes. Pain may become localized or constant if the bowel becomes ischemic or perforated. Abdominal distension is highly suggestive, as is constipation. Patients commonly have nausea and vomiting, which varies in severity based on the location of the obstruction, with proximal SBOs presenting with more severe symptoms. Patients with complete obstructions stop passing stool or flatus, although this may be delayed for 12-24 hours as the bowel distal to the obstruction continues to pass contents. Rarely, patients may have intermittent obstruction, often partial and low-grade, with spontaneous resolution of symptoms between episodes.

The greatest concern from an SBO is the risk of increased dilation leading to necrosis and bowel perforation. Patients with bowel ischemia or perforation typically present with more severe signs and symptoms, often with evidence of peritonitis, sepsis, and hemodynamic instability.